A hunting system preserved by lake-level rise in the Great Lakes basin

Silas Dunmore

Senior Field Observer, Submerged Landscapes, The Order of the Great Fifth Sea

Abstract

The Drop 45 Drive Lane site, located beneath modern Lake Huron along the submerged Alpena–Amberley Ridge, represents one of the most intact prehistoric hunting landscapes yet documented in the Great Lakes basin. The site comprises an approximately 20-acre network of stone alignments and drive lanes whose structure closely parallels large-game hunting systems documented in subarctic regions. Preservation beneath cold, low-oxygen waters has protected not only lithic features but also the potential survival of organic materials, offering rare insight into Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene subsistence strategies and social organization. The Drop 45 site further suggests that some of the most consequential human decisions in prehistory were made not at places of long-term occupation, but along routes—at landscapes designed for passage, interception and return.

Submerged prehistoric landscapes and Pleistocene–Holocene subsistence on the Alpena–Amberley Ridge, Lake Huron

Submerged prehistoric landscapes occupy an uneasy position within archaeological research. While increasingly acknowledged, they remain underrepresented owing to logistical constraints and methodological difficulty¹. In the Great Lakes region, post-glacial lake-level rise has concealed extensive terrestrial environments that once supported movement, subsistence and social coordination. These landscapes are often treated as peripheral because they no longer fall within conventional survey frames.

This imbalance reflects more than technical limitation. Archaeological attention has historically favoured places where people remained; settlements, camps and middens over places where people acted. Hunting corridors, interception zones and seasonal transit routes tend to resist architectural permanence. At Drop 45, the opposite has occurred. The absence of later reuse has preserved intention with unusual clarity. Even submerged, the site reads as purposeful. It does not require imaginative reconstruction to function just only careful attention.

The geological context of the Alpena–Amberley Ridge is central to this preservation. During the Late Pleistocene, glacial retreat, isostatic rebound and fluctuating hydrological regimes exposed a broad terrestrial corridor connecting what is now northeastern Michigan with southern Ontario². For several millennia, this ridge functioned as dry land, supporting tundra and boreal environments favourable to migratory ungulates, particularly caribou. Early Holocene lake-level rise gradually inundated the ridge, sealing former landscapes beneath cold, low-energy waters²,³. From an archaeological perspective, this inundation represents less a loss than a suspension. Processes that elsewhere erase evidence; ploughing, construction and repeated occupation simply did not occur. The ridge did not become abandoned; it became inaccessible. Palaeoenvironmental reconstructions from analogous regions indicate cooler and potentially drier climatic conditions during occupation, consistent with caribou-oriented subsistence strategies⁴.

Drop 45 was identified through systematic bathymetric and remote-sensing surveys rather than targeted site prospecting¹. High-resolution sonar revealed linear and curvilinear anomalies whose repetition, orientation and spatial coherence resisted geological explanation. Subsequent remotely operated vehicle (ROV) inspection and diver-based verification allowed ground-truthing without extensive disturbance⁵. During documentation it became apparent that the site resists interpretation at small scale. Individual features appear ambiguous in isolation. Only when mapped relationally does intention emerge. Drop 45 insists on being understood as a system.

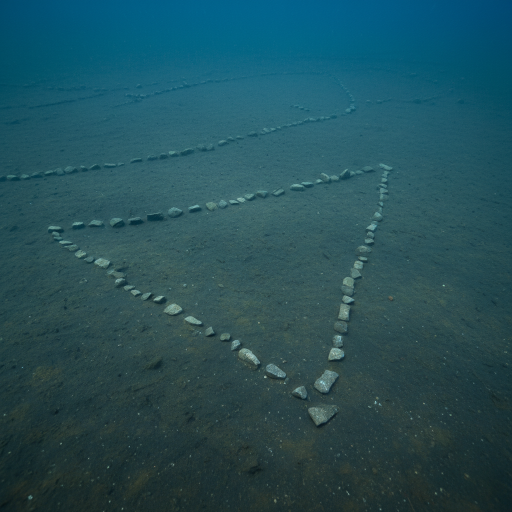

The complex extends across approximately 20 acres and consists of an interconnected network of stone alignments forming drive lanes, funnels and probable ambush zones⁵. These features are deliberately positioned to exploit subtle variations in topography and anticipated animal movement along the former ridge. V-shaped arrangements, extended linear walls and controlled openings recur throughout the site. The alignments do not announce themselves. They guide. Their effect would have been cumulative rather than abrupt, relying on repetition and constraint rather than force. This design is consistent with hunting systems intended to work with animal behaviour rather than against it.

Comparable communal hunting systems are well documented in subarctic and Arctic regions, particularly those associated with caribou exploitation⁵. These systems rely on guiding animals along predictable paths towards constrained kill zones using stone alignments as visual and behavioural cues. Behavioural ecology studies show that caribou respond consistently to linear landscape features, aggregating and moving directionally along edges whether natural or anthropogenic⁶,⁷. The value of comparison here is not analogy for its own sake, but functional convergence. Where landscapes, prey behaviour and seasonal predictability align, similar solutions tend to follow. Drop 45 fits this pattern with little need for interpretive overreach.

Preservation conditions at the site are exceptional. The lakebed environment is cold, deep and predominantly anaerobic, significantly inhibiting microbial activity and chemical degradation⁸. Such conditions enhance the preservation of organic materials otherwise unlikely to survive in open-air contexts. Research on waterlogged archaeological wood and bone demonstrates that submerged, low-oxygen environments can preserve organic components with remarkable fidelity⁹. Preservation is neither uniform nor guaranteed, however. The value of Drop 45 lies not in the promise of recovery, but in the opportunity to ask questions that terrestrial preservation rarely permits.

The scale and coherence of the system imply organized, cooperative hunting strategies. Construction alone would have required collective labour, planning and shared knowledge. Comparable large-game kill sites elsewhere in North America demonstrate similar demands on social coordination¹⁰. What is most striking is not the scale of coordination implied, but its restraint. The system appears designed to manage uncertainty in animal movement, weather and group size, rather than eliminate it. Seasonal variation likely structured participation, with larger spring migrations requiring broader cooperation and autumn hunts managed by smaller groups⁵.

Chronological placement of Drop 45 relies primarily on the potential recovery and analysis of preserved organic materials. Submerged contexts introduce challenges, including limited sampling opportunities and the possibility of old-carbon effects. Bayesian chronological modelling integrating multiple dating streams offers a promising framework for future analysis¹¹. In this context, chronological ambiguity should not be treated as failure. The interpretive value of the site lies in its placement within a narrow window of environmental and cultural transition, not in annual precision.

Drop 45 reinforces a broader conclusion: submerged landscapes are not archaeological absences, but archival spaces¹. The reluctance to treat them as cultural terrain reflects a modern division between land and water that did not exist for the people who built sites like Drop 45. The Great Lakes conceal extensive evidence of organized land use, movement and adaptation. To exclude these landscapes from archaeological synthesis is not methodological caution, but omission.

The conditions that preserved Drop 45 also render it vulnerable. Ethical frameworks increasingly emphasize restraint, particularly where destructive sampling offers diminishing returns¹². At Drop 45, preservation is not a passive condition but an active responsibility. The site has endured precisely because it was left alone. Research strategies must therefore privilege non-invasive documentation, long-term monitoring and conservative management¹³. Once disturbed, a submerged site cannot be resealed¹⁴.

The Drop 45 Drive Lane site provides compelling evidence of sophisticated prehistoric land use preserved beneath Lake Huron. Its scale, organization and preservation challenge long-standing assumptions about where meaningful archaeological records are found. What was once a terrestrial hunting ground remains legible beneath the water. If anything, the lake has preserved what later centuries might have erased. The challenge moving forward is not whether such sites can be found, but whether they can be recognized for what they are: integral components of human history that simply occupy a different plane.

Methods

The Drop 45 Drive Lane site was documented using a non-invasive, multi-scalar underwater archaeological approach combining high-resolution bathymetric mapping, side-scan sonar survey and targeted visual verification, following established micro-regional methodologies for submerged site archaeology¹. Sonar data were analysed to identify linear and curvilinear anomalies inconsistent with natural geomorphology, which were subsequently examined using remotely operated vehicle (ROV) imaging and diver-based ground-truthing to confirm cultural origin and feature continuity⁵. Site boundaries and internal organization were defined through relational spatial analysis rather than isolated artifact recovery. Geological and palaeoenvironmental context was reconstructed using published stratigraphic frameworks for Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene lake-level change and ridge exposure²,³, with climatic analogues drawn from high-resolution palaeoenvironmental studies in comparable post-glacial settings⁴. Preservation potential was assessed by reference to established taphonomic models for anaerobic, waterlogged environments⁸,⁹. No excavation or destructive sampling was conducted, and all documentation prioritized minimal disturbance in accordance with contemporary ethical and conservation guidelines¹²–¹⁴.

Author contributions

S.D. conceived the study, synthesized geological, archaeological and behavioural evidence, and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

References

O’Shea, J. M. Micro-regional approaches for submerged site archaeology. J. Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 16, 103–117 (2020).

Karrow, P. F., Dreimanis, A. & Barnett, P. J. A proposed diachronic revision of Late Quaternary time-stratigraphic classification in the eastern and northern Great Lakes area. Quat. Res. 54, 1–12 (2000).

Oviatt, C. G. & Pedone, V. A. Chronology of the early transgressive phase of Lake Bonneville. Quat. Res. 121, 32–39 (2024).

Druzhinina, O. et al. Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene palaeoenvironmental evolution in the SE Baltic region. Boreas 49, 544–561 (2020).

O’Shea, J. M. et al. A 9,000-year-old caribou hunting structure beneath Lake Huron. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 6911–6915 (2014).

Fortin, D. et al. Movement responses of caribou to human-induced habitat edges. Am. Nat. 181, 827–836 (2013).

McKay, T. L. et al. Landscape features associated with central mountain caribou mortalities. Ecol. Evol. 11, 2234–2248 (2021).

Butterfield, N. J. Organic preservation of non-mineralizing organisms and the taphonomy of the Burgess Shale. Paleobiology 16, 272–286 (1990).

Sidoti, G. et al. Inorganic component in oak waterlogged archaeological wood and volcanic lake compartments. Biogeosciences 20, 3137–3149 (2023).

Kooyman, B. et al. Late Pleistocene horse hunting at the Wally’s Beach site. Am. Antiquity 71, 101–121 (2006).

Andreaki, V. et al. Absolute chronology at the waterlogged site of La Draga. Radiocarbon 64, 907–948 (2022).

Pálsdóttir, A. H. et al. Not a limitless resource: ethics and guidelines for destructive sampling. R. Soc. Open Sci. 6, 191059 (2019).

Macgregor, C. Preserving the Ancient Human Trackways Site. Stud. Conserv. 67, 150–155 (2022).

Walka, J. J. Management methods and opportunities in archaeology. Am. Antiquity 44, 575–582 (1979).