The Order of the Great Fifth Sea

Filed Under: Maritime Heritage & Methodology Integrity

Date: December 10, 2024

Author: Alistar Corvus

Against the Age of Aerial Shortcuts

In recent months, there has been an unseemly proliferation of “discoveries” of Great Lakes shipwrecks announced with all the subtlety of a brass band in a library. The common denominator in these so-called triumphs is not discipline, heritage, or scholarly rigor — but rather the increasingly casual deployment of aerial reconnaissance by means of ultralight aircraft, recreational drones, and other airborne conveniences designed to bypass the very work that makes discovery meaningful.

The Order regards this trend with a blend of scholarly caution and practical objection.

From an academic standpoint, such methods reduce the discipline of maritime heritage work to a form of industrial scanning — effective, perhaps, for compiling a list of coordinates, but utterly bankrupt in terms of context, interpretation, and cultural stewardship. The aerial observer, peering from a mechanical contraption at several hundred feet, is denied the vital dialogue between investigator and environment: the subtle shifts of light on water, the cadence of waves against a shoreline, the serendipitous clue found only by trudging along the littoral zone with cold wind in one’s face.

From a practical and ethical standpoint, these methods carry hazards that their practitioners too often neglect to mention. Ultralights and low-flying craft produce both air and water noise pollution, disrupting bird nesting colonies and aquatic habitats. The risk to the pilot is hardly negligible; a sudden engine failure over open water offers limited prospects for graceful recovery.

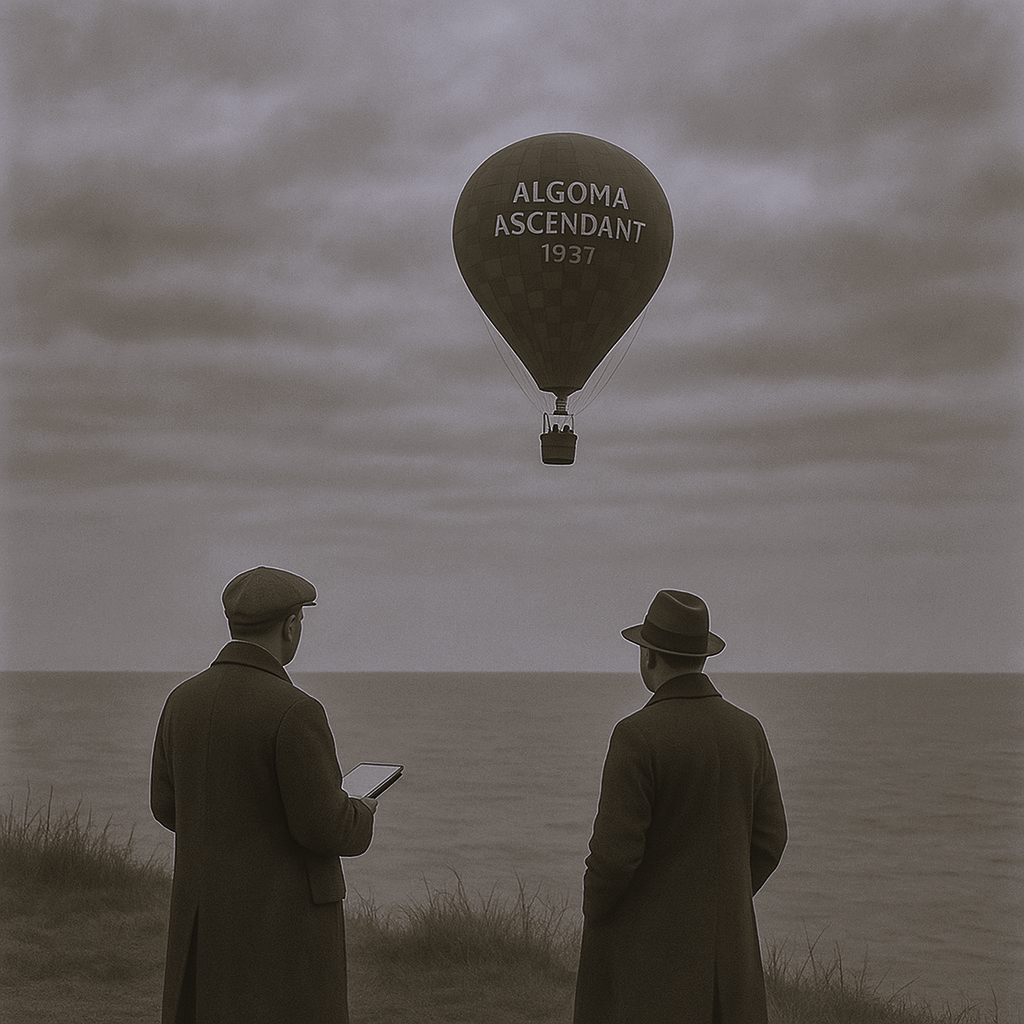

Indeed, the Order is not without direct experience in such matters. In the late summer of 1937, we briefly experimented with aerial reconnaissance in the form of the Algoma Ascendant — a hot air balloon equipped with a large plate camera, designed to capture shoreline wreck outlines at low tide equivalents. The craft’s maiden voyage ended abruptly when shifting winds forced a landing attempt offshore; the balloon descended into Lake Michigan and, despite valiant handling by its crew, was lost to the depths. Both aeronauts were retrieved unharmed by a passing fishing vessel, and the Order determined thereafter that our explorations would remain sensibly anchored to the shore and deck.

Let it be understood: We are not Luddites, nor do we reject technology out of hand. But technology divorced from discipline, stripped of environmental responsibility and cultural context, is not heritage work — it is merely extraction.

We remain committed to the patient, deliberate methodologies that have served this body for over a century. The Fifth Sea does not yield her secrets to the impatient. Those who would seek them from the air may gain speed, but they lose something far more valuable: the slow apprenticeship to place and history without which all “discoveries” are but curiosities in a catalogue.

Member Comments

M.R.H.

Entirely concur. The aerial “find” is little more than the scavenger hunt equivalent of fast food — quick, cheap, and wholly unsatisfying. The very absence of environmental immersion strips the act of any dignity.

J.B.L.

The safety concerns cannot be overstated. I have witnessed ultralights come down in less-than-ideal conditions, and Lake Michigan is far less forgiving than these weekend pilots seem to appreciate. A strong onshore wind can turn enthusiasm into a rescue operation in a matter of minutes.

D.T.K.

While I am among those who rode in the Algoma Ascendant on her final, inglorious descent, I assure our newer members that the matter was not entirely without merit. However, the lesson remains: any platform that depends upon both wind direction and human optimism is inherently flawed.

C.S.P.

May I remind the Concordant that the wreck of the Ascendant remains unfound? If we truly wish to assert our commitment to heritage recovery, locating the remains of our own balloon would send an eloquent message — preferably without the assistance of a camera drone.

H.M.W.

The noise argument is valid. As an ornithologist by training, I cannot support any method that scatters nesting colonies or disturbs migration patterns for the sake of a “find” that could have been made with a pair of boots and a day’s patient observation.

P.L.E.

I still contend we could acquire an ultralight of our own, fly it once for the record, and then store it in the Chapter House foyer as a cautionary exhibit. Symbolism has its uses.